Corinna Gosmaro

15.02.2023 – 21.04.2023

Exhibition views

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (ground floor), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (ground floor), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (ground floor), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (ground floor), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (ground floor), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (ground floor), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (ground floor), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (basement), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (basement), photo by Giorgio Benni

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, installation view at The Gallery Apart Rome (basement), photo by Giorgio Benni

Works

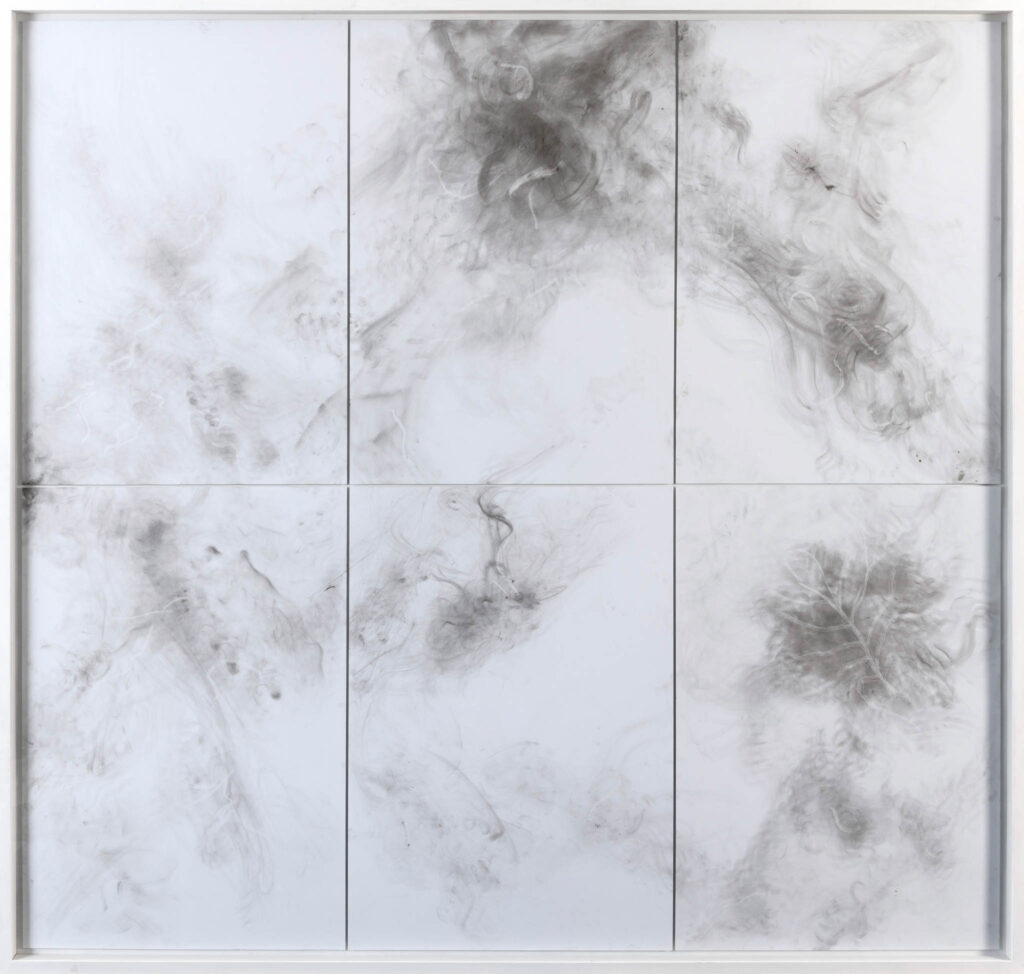

Nesting, 2023, mixed media on polyester filters, 205 x 191 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

Nesting, 2023, mixed media on polyester filters, 205 x 191 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

Nesting, 2022, mixed media on polyester filters, 205 x 191 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

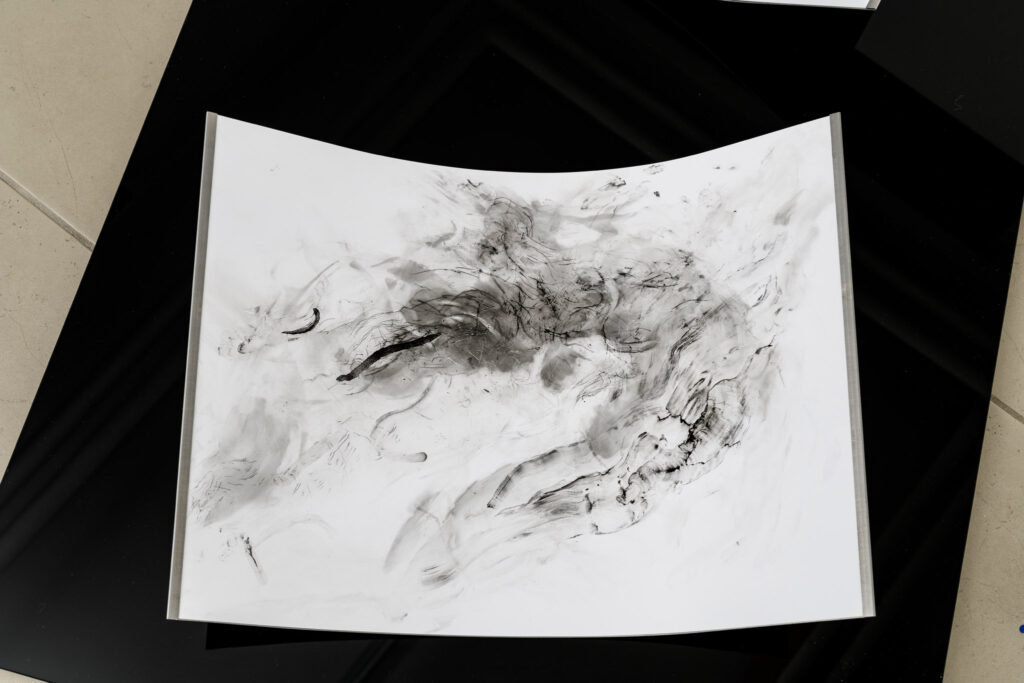

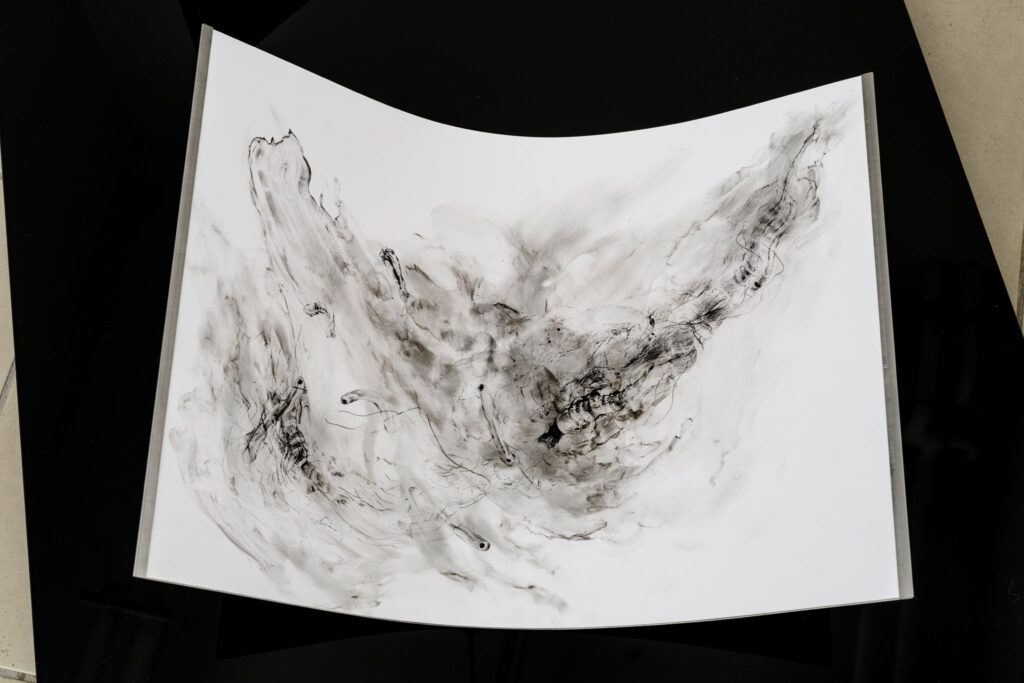

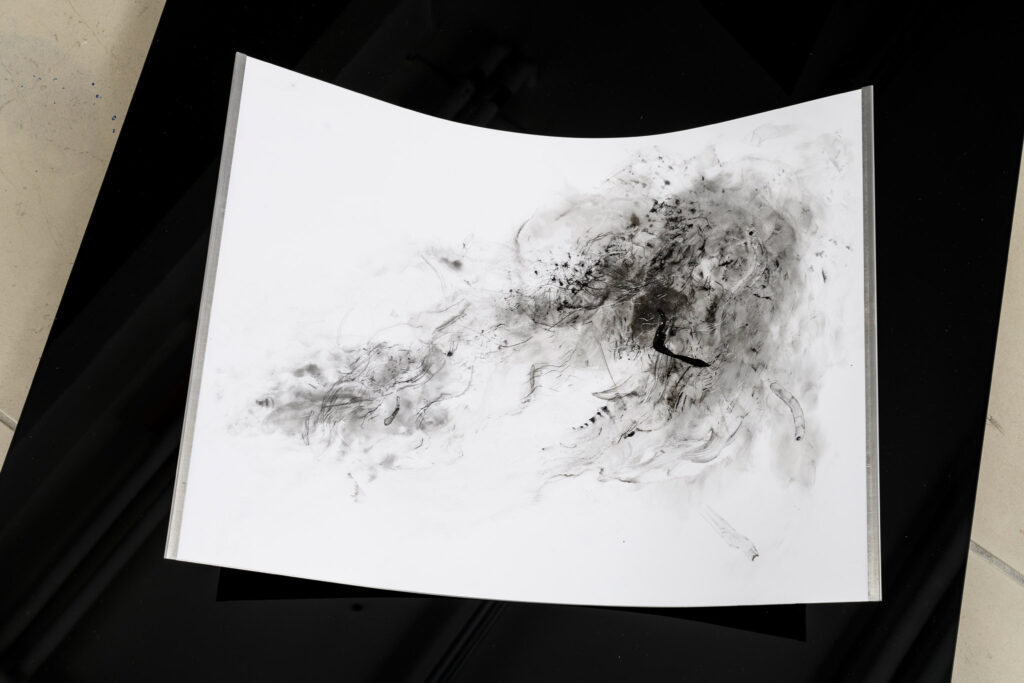

Mosche Volanti, 2023, direct etching and thin pigments on photographic paper, 187 x 92,5 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

Mosche Volanti, 2023, direct etching and thin pigments on photographic paper, 74,3 x 153,9 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

Nesting, 2023, mixed media on polyester filters, 141 x 161 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

Mosche Volanti (con gli occhi), 2021, direct abrasion on photographic paper and thin pigment, 209 x 210 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

In spite of your poor eyes, 2023, direct etching and thin pigments on photographic paper and iron, 42 x 51,5 x 15 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

In spite of your poor eyes, 2023, direct etching and thin pigments on photographic paper and iron, 42 x 51,5 x 15 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

In spite of your poor eyes, 2023, direct etching and thin pigments on photographic paper and iron, 42 x 51,5 x 15 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

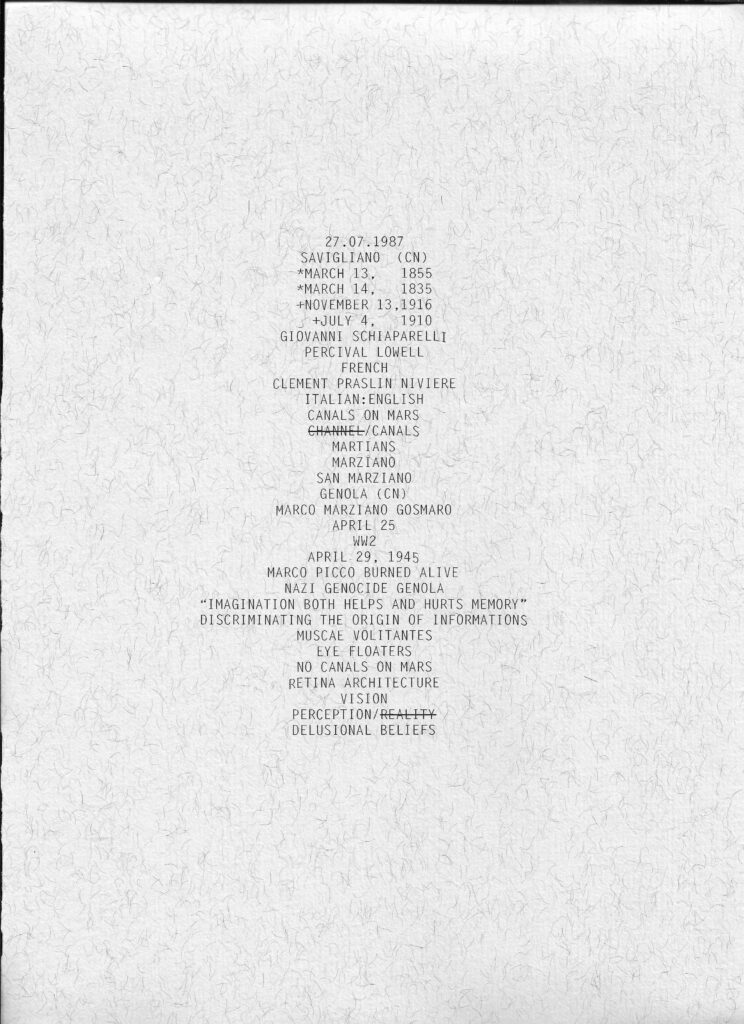

Delusional Beliefs, 2023, projection on paper, 30,5 x 22,5 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

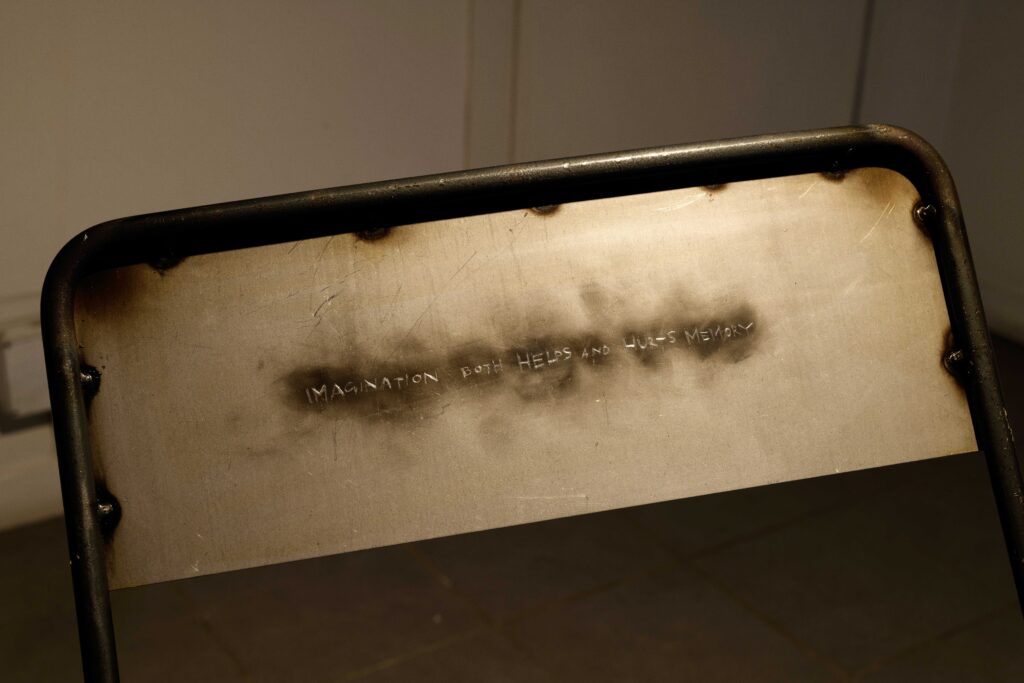

Imagination Both Helps and Hurts Memory, 2023, direct engraving on metal and thin pigments, 88,5 x 62 x 42,5 cm, photo by Giorgio Benni

Imagination Both Helps and Hurts Memory, 2023, detail, photo by Giorgio Benni

The Gallery Apart is proud to announce the third solo show by Corinna Gosmaro. In line with the previous exhibits, in particular the 2020 Chutzpah! exhibit, and Conversation Piece Part VI of the same year hosted in the Fondazione Memmo, the artist continues to explore the meanders of the elaboration of reality and once again she plays with the inevitable shift between reality and our own perception.

Gosmaro finds a relation, almost a coincidence, between her recent production and the story whose protagonists are the only two scientists in the world who could see canals on Mars: Percival Lowell, American author, mathematician and astronomer, and the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, the first to claim the existence of the so-called Martian “canals” that took shape in his sketches. Lowell, who was aware of Schiaparelli’s failing eyesight, committed to pursuing the observation of the planet.

Today we know that there are no canals upon the planet, and that there is no form of intelligent life on Mars that created them. However, Lowell’s enthusiasm, who was also deceived by a fatal mistranslation, led him to believe that the Red Planet was home to an advanced civilization. As Lowell read the word ‘canali’ in the Italian book by Schiaparelli, Lowell mistranslated it into canals, a word that in English suggests artificial origin, and not channel, which has a more general meaning. A translation error full of consequences: «Martians build two immense canals in two years. Vast engineering works accomplished in an incredibly short time by our planetary neighbors» the New York Times from 27 August 1911 headlined the interview to Lowell.

Behind the translation error and the enthusiasm for a potential discovery, there is an even more dumbfounding error: the telescopes used by Lowell and Schiaparelli served also as optical devices that projected the neurovascular structures of their own eyes. Then the two scientists had been mapping the reflections of blood vessels in their eyes and the structure of their own retina. In addition, they had been observing their own eyes, they were deceived by their own perception. Thus, lights and shadows became spots forming streaky lines and that inspired theories and countless works of science fiction such as The War of the Worlds, which appealed to thousands of Americans, who as they listened to the radio broadcast by Orson Welles on Halloween night in 1938 were frightened into believing Martians had invaded New Jersey.

On the one hand, Gosmaro investigates the relationship and the distance between what we perceive visually and what we want to perceive and see. On the other hand, she focuses on the absolute value of the yearning for the exploration and therefore for vision. The two possible perspectives of intellectual development could be epitomized by the difference between the English phrases bias for, meaning inclination or predilection, and bias against, meaning prejudice and preconception. Thus, perception and the study of its mechanisms are important because perception is the first step in the cognitive process and, based on the path taken, we can give way to imagination to formulate phantasmagorical theories, supported however by a sincere inspiration to search for the truth, or we can let ourselves be influenced by prejudice that inevitably leads to anti-science and conspiracy.

To Gosmaro, the interpretations on the Canals of Mars are a metaphor for the effort that our species makes to find a more structured organization of confused realities. As highlighted by Gombrich in art and by Lowell himself in science, it is easy to see what we expect to see. Visual experience is rooted in social conditionings (trends, prejudices, fears, religious and political precepts), but the cognitive process cannot exclude this experience across the path that, at individual level, leads to exercise our judgement skills whose results are generally overrated and their adherence to reality is not examined.

The passage from visual experience to the development of a convincement, whether it is true knowledge or devotedness to beliefs, is strongly influenced by the sources of perception (direct experiences, personal relationships, studies, meditation and even dreams) and it materializes as a flow of consciousness from the internal to the external world that everyone finally rinses in our personal memories, in what we are convinced to be our subjective experiences but that is often influenced by mistakes, forgetfulness, and distortions. Sometimes it is not possible to distinguish what we have perceived from what has been created artificially. Gosmaro this time goes backwards to search for forced coincidences and longed-for surprises.

The artist presents more series of works that invite the beholders to abandon themselves to this perceptive flow without any orientation in the personal visual experience.

In the new filters Nesting the image takes shape, with no orientation, among the meshes of the polyester filter with oil and spray painting, trying to increase the interpretation potentialities with the beholder’s imagination who is attracted into the depth of the material to glimpse and to read freely.

Gosmaro’s interest in archetypical images remerges and she gives shape to Gombrich’s precept that “The reproduction of the most simple images does not represent a simple psychological process.”

A further series of works allow Gosmaro to formalize the eye floaters phenomenon, black dots in the visual field that float away when one tries to focus on them. A common example of the distance between reality and vision that the artist translates into bidimensional works that are revealed through movement and other works that visitors can hold in their hands and move under the source of light so as to augment their perception.

Finally, two metal sculptures, two chairs that seem to be kneeling as if to stage either a bow to the enthusiasm of the two scientists or the surrender to the impossibility to go beyond our own illusions, on which Imagination both helps and hurts memory is carved exemplifying the true meaning of the exhibition.

The exhibition is named after the artwork Delusional Beliefs, which is the conjunction element between the two floors in the gallery and which, through the exhibition of a series of (un)expected coincidences, becomes the conceptual pivot that suggests the paradox of a reality that, the more it seems to be motionless, the more it exhibits the unpredictable oscillations between the moments of perception.

The Gallery Apart è orgogliosa di annunciare la terza personale in galleria di Corinna Gosmaro. In continuità con le precedenti esposizioni, in particolare nelle mostre Chutzpah! del 2020 e Conversation Piece Part VI dello stesso anno presso la Fondazione Memmo, l’artista prosegue la sua ricerca nei meandri dell’elaborazione della realtà e gioca ancora una volta con lo scarto inevitabile che si interpone tra il reale e la nostra percezione.

Gosmaro trova una corrispondenza, quasi una coincidenza, tra la sua recente produzione e la vicenda che vede protagonisti gli unici due scienziati al mondo in grado di vedere canali su Marte: Percival Lowell, letterato, matematico e astronomo americano, e l’astronomo italiano Giovanni Schiaparelli, primo ad ipotizzare e disegnare i cosiddetti Canali di Marte. Lowell, consapevole del declino della vista di Schiaparelli si incarica di proseguire l’osservazione del pianeta.

Oggi sappiamo con certezza che non esistono canali su Marte, così come non esiste una forma di vita intelligente capace di crearli, ma all’epoca l’ardore di Lowell, spinto anche da un fatale e semplice errore di traduzione, lo portò alla convinzione della presenza di una civiltà sul Pianeta rosso. Leggendo nel testo italiano di Schiaparelli la parola canali, Lowell la tradusse con canals che in inglese prevede un’origine artificiale e non channel, che ha significato più generale. Un errore di traduzione gravido di conseguenze: «I Marziani costruiscono due immensi canali in due anni. Immensi lavori di ingegneria fatti in un tempo incredibilmente breve dai nostri vicini planetari» è il titolo dell’intervista a Lowell sul New York Times del 27 agosto 1911.

Dietro l’errore di traduzione e la spinta inebriante di una possibile scoperta, si nasconde un errore ancora più sorprendente: gli strumenti di osservazione utilizzati da Lowell e Schiaparelli funzionavano anche da dispositivo ottico, proiettando le strutture neurovascolari dei loro stessi occhi. I due scienziati non mappavano altro che le ombre dei propri vasi sanguigni e l’architettura della loro stessa retina. Non solo, osservavano ignari la loro stessa visione, erano in balia della loro percezione. Ed ecco che luci e ombre diventano punti, che si uniscono in linee, che si strutturano in diramazioni, che danno adito a teorie che ispirano romanzi come “La guerra dei mondi”, capaci di muovere masse di migliaia di americani, che nel 1938 ascoltando la trasmissione radiofonica di Halloween di Orson Welles temono davvero che i marziani siano sbarcati nel New Jersey.

Gosmaro si interroga da una parte sul rapporto e sulla distanza tra ciò che si percepisce visivamente e ciò che si vuole percepire e vedere, dall’altra sul valore assoluto dell’anelito alla ricerca e dunque alla visione. Le due possibili prospettive di sviluppo intellettuale potrebbero riassumersi nella differenza tra le espressioni inglesi bias for, che attesta una propensione o una predilezione, e bias against, che indica pregiudizio e preconcetto. Da qui l’importanza della percezione e dello studio dei suoi meccanismi, giacché la percezione è il primo passo nel processo cognitivo e, a seconda della direzione intrapresa, si può dare spazio all’immaginazione finalizzandola alla formulazione di teorie fantasmagoriche, comunque sorrette da sincero afflato verso la ricerca della verità, oppure farsi condizionare dal pregiudizio che conduce inevitabilmente verso l’antiscienza e il complottismo.

Le interpretazioni sui Canali di Marte sono per Gosmaro una metafora dello sforzo che la nostra specie compie nel tentativo di dare un’organizzazione strutturata a realtà confuse. Come evidenziato da Gombrich in ambito artistico e dallo stesso Lowell sul piano scientifico, è facile che si veda ciò che ci si aspetta di vedere. L’esperienza visuale affonda le radici nei condizionamenti (mode, pregiudizi, paure, precetti religiosi e politici), ma il processo cognitivo non può prescindere da tale esperienza nel percorso che sfocia, a livello individuale, nell’esercizio della propria capacità di giudizio i cui i risultati sono tendenzialmente sopravvalutati e non esaminati in merito alla loro effettiva aderenza alla realtà.

Il passaggio dall’esperienza visuale alla formazione di un convincimento, sia esso vera conoscenza o adesione a credenze, è fortemente influenzato dalle fonti di percezione (esperienze dirette, relazioni personali, media, studi, meditazioni e persino sogni) e si concretizza in un flusso di coscienza dall’interiore al mondo esterno che ciascuno infine risciacqua nei ricordi individuali, in quello che si è convinti essere il proprio vissuto ma che spesso è influenzato da errori, dimenticanze e distorsioni. A volte non è possibile distinguere ciò che si è percepito da ciò che è stato artificiosamente creato. Gosmaro questa volta gioca a ritroso e va alla ricerca di coincidenze forzate e sorprese cercate.

L’artista presenta in mostra più serie di opere che invitano lo spettatore ad abbandonarsi a questo flusso percettivo senza orientamento nell’esperienza visuale personale.

Nei nuovi filtri Nesting (annidamento) l’immagine si compone, anche qui senza orientamento, tra le maglie del filtro di poliestere con olio e pittura a spray, cercando di aumentare le potenzialità interpretative sintonizzandosi con l’immaginazione dello spettatore che viene richiamato nella profondità del materiale a intravedere e a leggere liberamente.

In ciò riemerge l’interesse di Gosmaro per le immagini archetipiche con cui dà forma al precetto di Gombrich secondo cui “La riproduzione delle figure più semplici non costituisce affatto un processo in sé psicologicamente semplice”.

Un’ulteriore serie di opere consente a Gosmaro di formalizzare il fenomeno delle mosche volanti, corpuscoli neri e mobili che invadono la vista senza mai consentire una loro messa a fuoco. Un esempio comune della distanza tra realtà e visione che l’artista traduce in opere bidimensionali che si rivelano con il movimento e altre che lo spettatore può prendere in mano e muoverle sotto la fonte di luce in modo da aumentarne la percezione.

Infine, due sculture in metallo, due sedie che paiono inginocchiate quasi a inscenare o un inchino all’ardore dei due scienziati o l’arresa all’impossibilità di andare oltre le nostre stesse illusioni, sulle quali è incisa la scritta Imagination both helps and hurts memory che ben racchiude il senso profondo della mostra.

Delusional Beliefs, opera che dà il titolo alla mostra, è l’elemento di congiunzione tra i due piani della galleria e, attraverso l’esposizione di una serie di coincidenze (in)attese, diventa il perno concettuale che suggerisce il paradosso di una realtà che, quanto più ci appare immobile, tanto più esibisce le imprevedibili oscillazioni fra i momenti della percezione.

share on