Cesare Pietroiusti

03.04.2025 — 31.05.2025

The Gallery Apart è orgogliosa di annunciare “Materia paterna” la seconda mostra personale di Cesare Pietroiusti negli spazi della galleria.

Sulla scia della precedente mostra “Valori”, parzialmente incentrata sulla complessità del rapporto padre/figlio filtrato attraverso la paterna collezione di francobolli, Pietroiusti indaga ancora più in profondità la sua relazione con i genitori, in modo palese rispetto alla figura paterna, ma con un significativo riferimento alla madre, ironicamente evocata attraverso il termine “materia”. Nulla può fungere da introduzione alla mostra meglio del testo scritto per l’occasione dall’artista.

La decisione di dedicare una mostra alla figura paterna – non al padre in generale, ma proprio al proprio padre – al netto di probabili determinanti inconsce, richiede un’occasione.

In questo caso, è stata il fatto di avere dovuto svuotare, dopo averlo venduto, l’appartamento in via Novara, nel “signorile” quartiere Trieste di Roma, a pochi passi dal Museo Macro, dove avevano vissuto i nonni materni e, dalla mia nascita in poi, i miei genitori. In quella casa mio nonno è morto nel 1963, mia nonna nel 1986, mio padre nel 2011, e mia madre quattro anni fa. Tutti gli ambienti erano pieni di oggetti le cui storie, funzioni, apparenze, attraversano tre generazioni – dai primi agli ultimi anni del ventesimo secolo. Ho buttato via molto, ma molto ho tenuto, nella speranza di trovare documenti interessanti o sorprendenti, magari in grado di fare luce su aspetti a me sconosciuti di qualche componente della famiglia. Così, in cantina, in un paio di voluminosi scatoloni coperti di fuliggine nera, ho trovato centinaia di fascicoli con le pubblicazioni scientifiche (1960-1966) di mio padre, Guido Pietroiusti.

Guido era medico, ginecologo (ma lui preferiva definirsi “ostetrico”) di successo, a lungo primario, negli anni più felici della sua vita professionale, dell’Ospedale di Velletri. Non era un grande oratore, né un raffinato intellettuale, ma certamente era un ottimo medico, molto stimato e amato dalle sue pazienti. Ricordo, in particolare, la sua capacità di rassicurare le partorienti nei momenti decisivi del travaglio. Era convinto che avrei fatto anche io l’ostetrico e quando – credo fossi al secondo anno di università e, per inciso, assai in ritardo nella maturazione sessuale – mi portò nel suo reparto e provò a insegnarmi come si fa una visita ginecologica, fui sopraffatto dall’imbarazzo, dal senso di inadeguatezza e di incolmabile distanza tra me (le mie dita) e la possibilità di dare un senso di qualunque genere a ciò che stavo facendo. In effetti quella distanza non si è mai colmata e forse il fatto che io abbia fatto l’artista e non il medico, è anche dovuto a quel trauma.

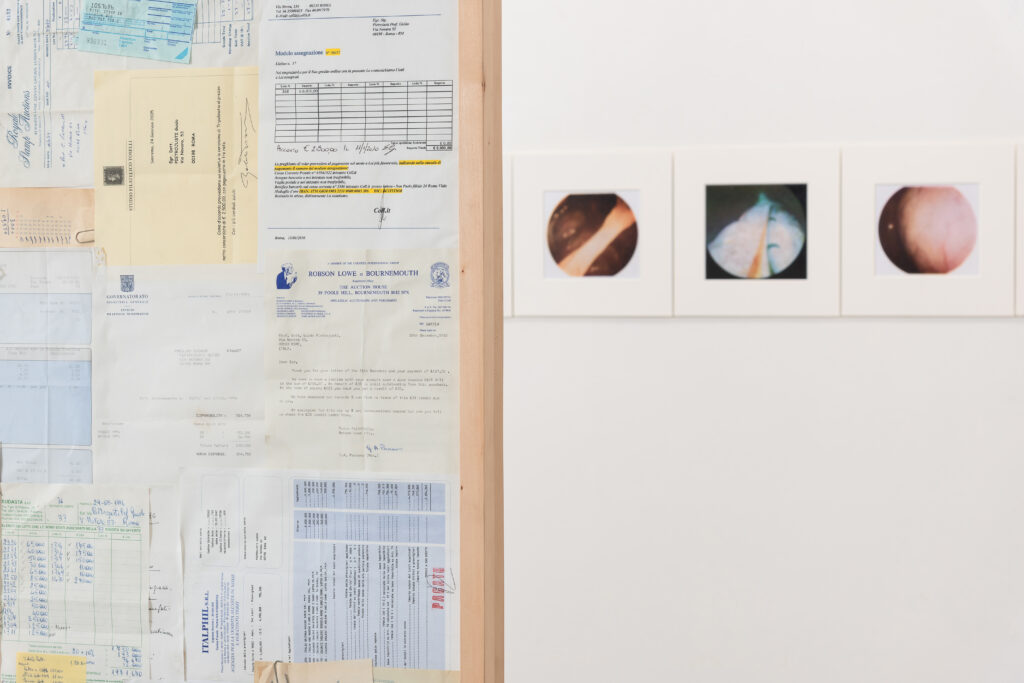

Alcune delle pubblicazioni paterne raccontano di una nuova tecnica, appresa in Francia, la celioscopia: un modo, in seguito diventato molto comune, di esplorare l’apparato genitale femminile per “via endoscopica” praticando un foro nell’addome e facendovi passare un piccolo obiettivo collegato a una foto- o video-camera. Nella pubblicazione “L’importanza della celioscopia nella diagnostica ginecologica” la tecnica è illustrata sia con immagini a colori degli organi interni, sia con alcune foto in bianco e nero del setting operatorio, in una delle quali si vede mio padre con l’occhio incollato a una macchina fotografica precariamente connessa a un tubo che penetra nell’addome di una persona in anestesia totale, il cui corpo è, per il resto, coperto. Questa immagine, e la serie di “celiofoto” riprodotte in questo e in altri fascicoli, mi hanno fatto venire in mente che, tra il 1989 e metà anni ’90 avevo esposto, in varie occasioni in gallerie e musei, le riproduzioni fotografiche di quello che c’era dall’altra parte delle pareti degli spazi espositivi.

Il progetto di questa mostra “Materia paterna” emerge quindi dall’idea di un confronto, e forse da un tentativo di dare forma a una affinità che, data l’evidente distanza rispetto a scelte professionali e valoriali, risulta – almeno per me – inattesa e sorprendente.

“Materia paterna” diventa così un progetto che sta fra l’omaggio e la sottolineatura critica di una differenza sostanziale, fra la nostalgia e l’ironia di ripercorrere una vicenda punteggiata da brandelli di memoria, attraverso il ri-utilizzo, la manipolazione, la ri-configurazione di oggetti altrimenti destinati alla discarica. Come se l’arte potesse, con una libertà che neanche la ricerca scientifica possiede, dare senso a una materia altrimenti incomprensibile o non maneggiabile, inservibile o intoccabile.

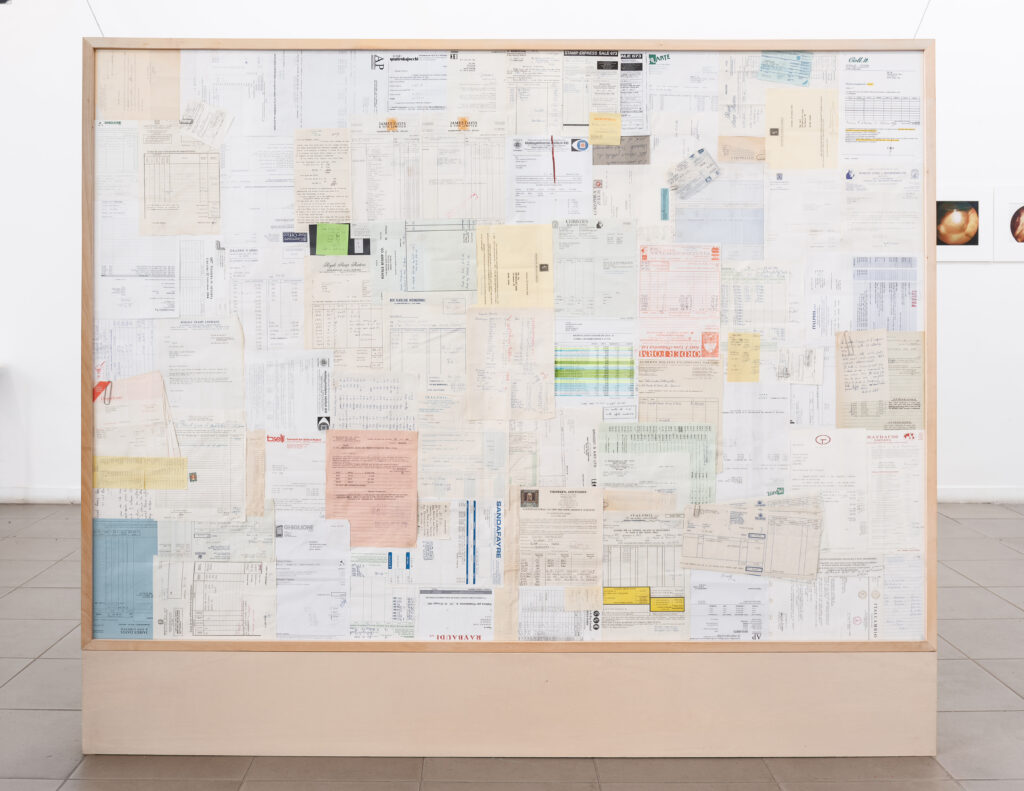

La mostra presenta un vasto corpo di opere, alcune storiche ma in gran parte di nuova produzione. Quasi a certificare il trait d’union con la precedente mostra in galleria, l’artista ha realizzato un’opera di grandi dimensioni consistente in due collages posizionati l’uno contro l’altro, come due facce di un’enorme busta, e contenenti rispettivamente decine di involucri postali provenienti da case d’asta o mercanti di francobolli e decine di lettere e fatture attestanti le acquisizioni del padre per la sua collezione.

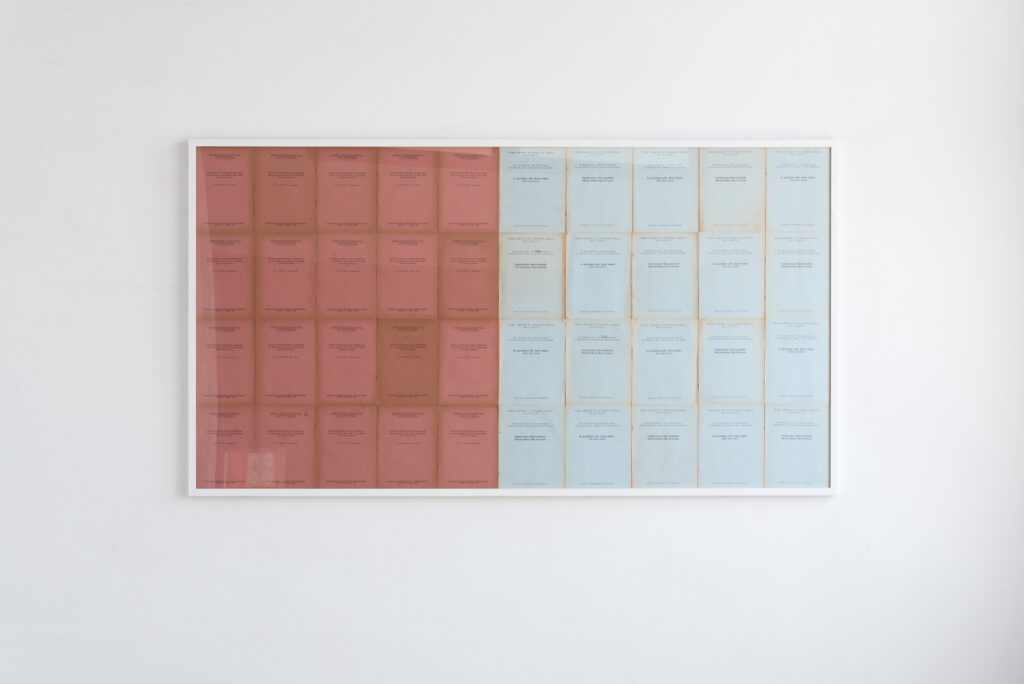

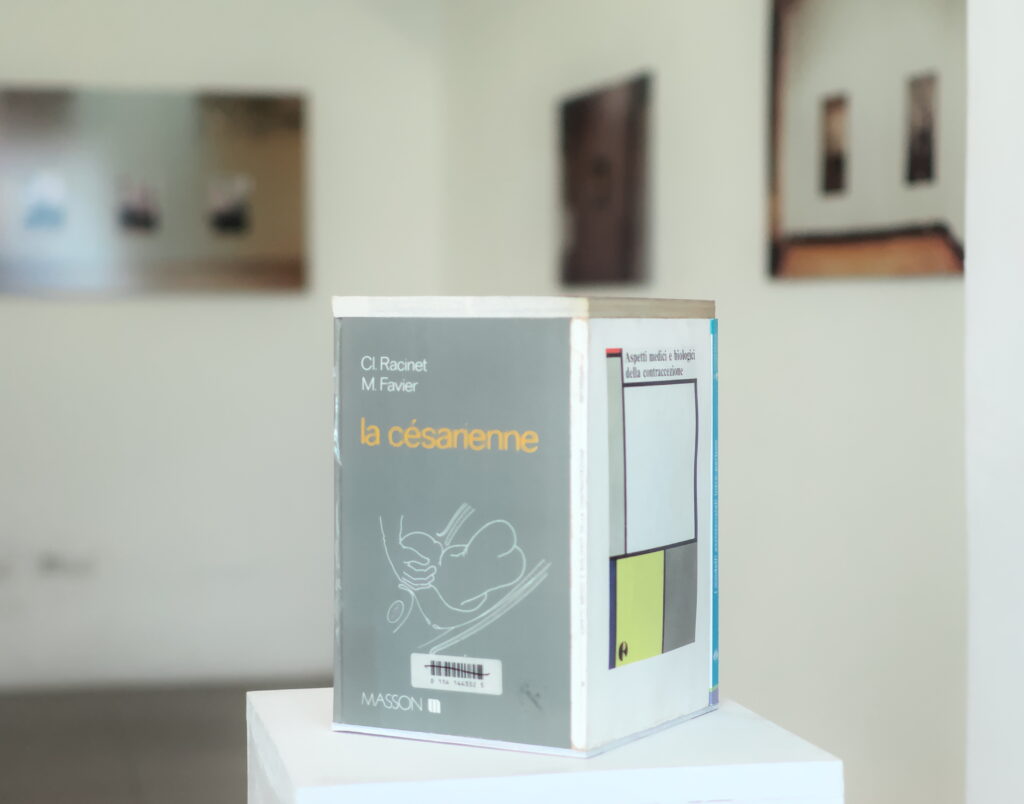

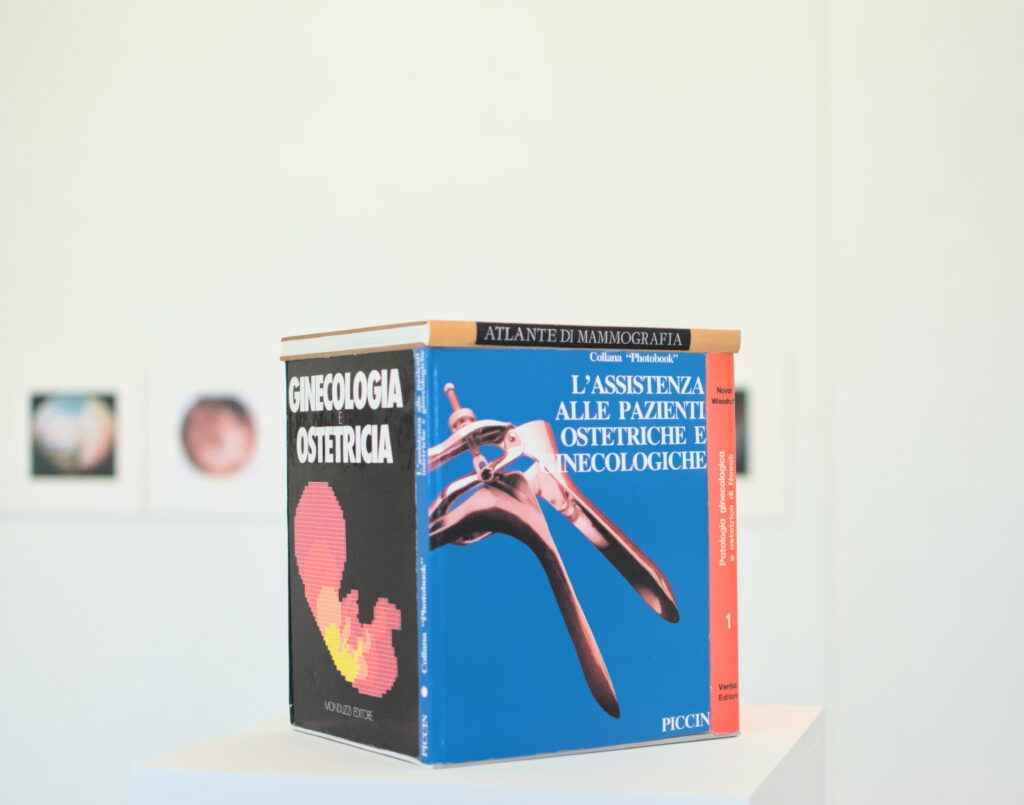

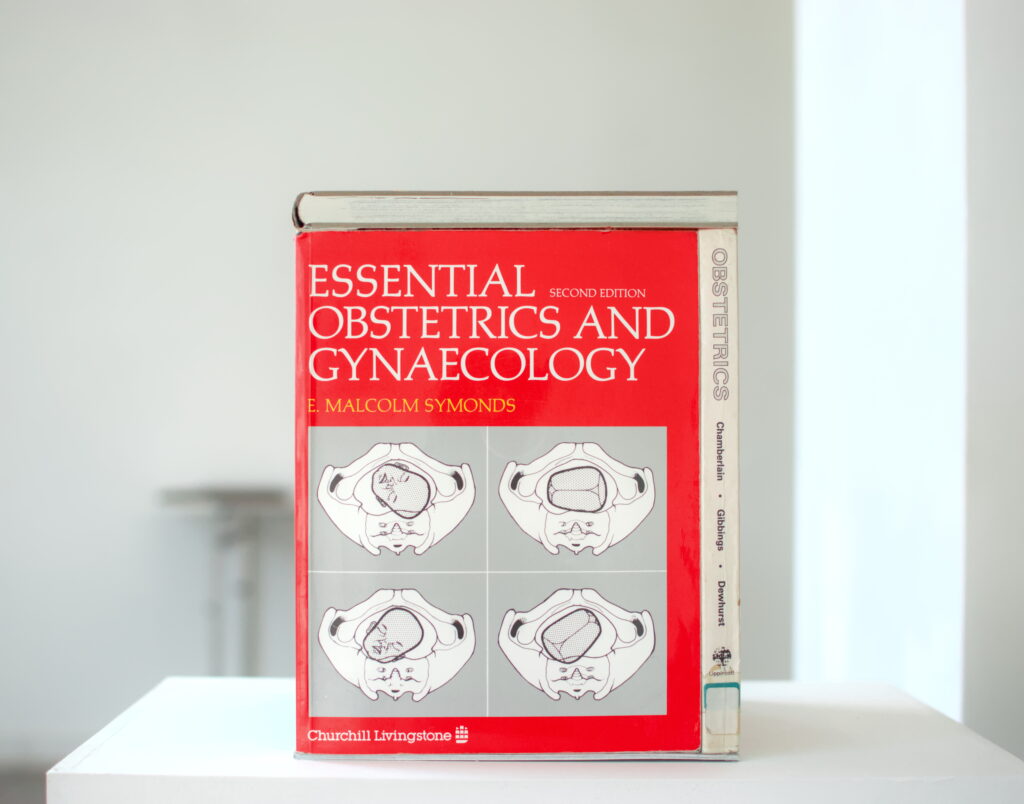

Gran parte della mostra focalizza l’attività medica paterna. Avendo trovato un consistente numero di pubblicazioni del padre e di libri della sua biblioteca, Pietroiusti ha utilizzato le pubblicazioni scientifiche per realizzare un grande collage in cui ripetizione e bicromia danno vita ad un’opera a metà tra concettuale e astratto-geometrico, mentre i libri hanno preso nuova vita in una serie di sculture volumetricamente regolari.

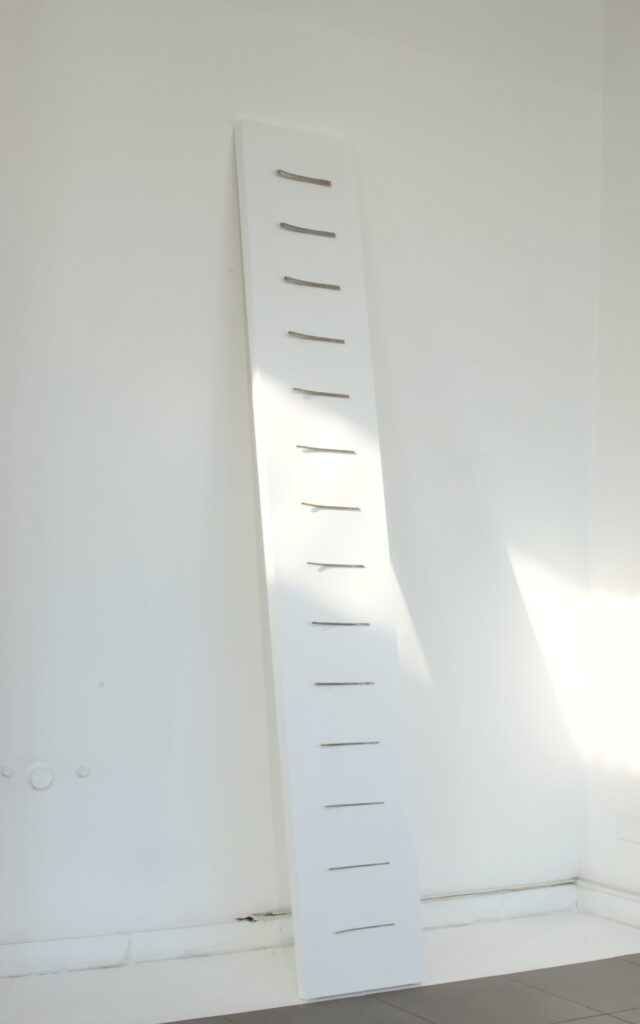

Una serie fotografica si basa invece sulla riproduzione delle immagini trovate dall’artista e realizzate dal padre con la tecnica della celioscopia. Gli organi interni si rivelano scenario di una enigmatica bellezza, dando vita ad immagini che evocano lo spazio siderale. Direttamente connesso, il lavoro scultoreo ottenuto mettendo in fila, secondo una progressione dimensionale dal piccolo al grande, una serie di dilatatori uterini in acciaio, posizionati a comporre una sorta di scala ascendente. E sempre attraverso il ricorso ad oggetti trovati nello studio paterno, ecco un lavoro consistente in una proiezione in sequenza di 80 diapositive tutte titolate GINECOLOGIA presumibilmente usate per scopi didattici.

Questo corpus di lavori che riutilizzano oggetti residuali della lunga attività professionale del padre offre a Pietroiusti l’occasione per un’analisi di sé e del suo rapporto (mancato) con la medicina, ma spinge altresì a riflettere sul corpo femminile, sulla sua centralità rispetto all’universo conosciuto e al miracolo della vita (pensiamo a L’origine du monde di Courbet) ma anche sulla dialettica fra la tradizionale e patriarcale visione della femminilità come mistero e la interiorizzata consapevolezza del principio di autodeterminazione del proprio corpo da parte delle donne.

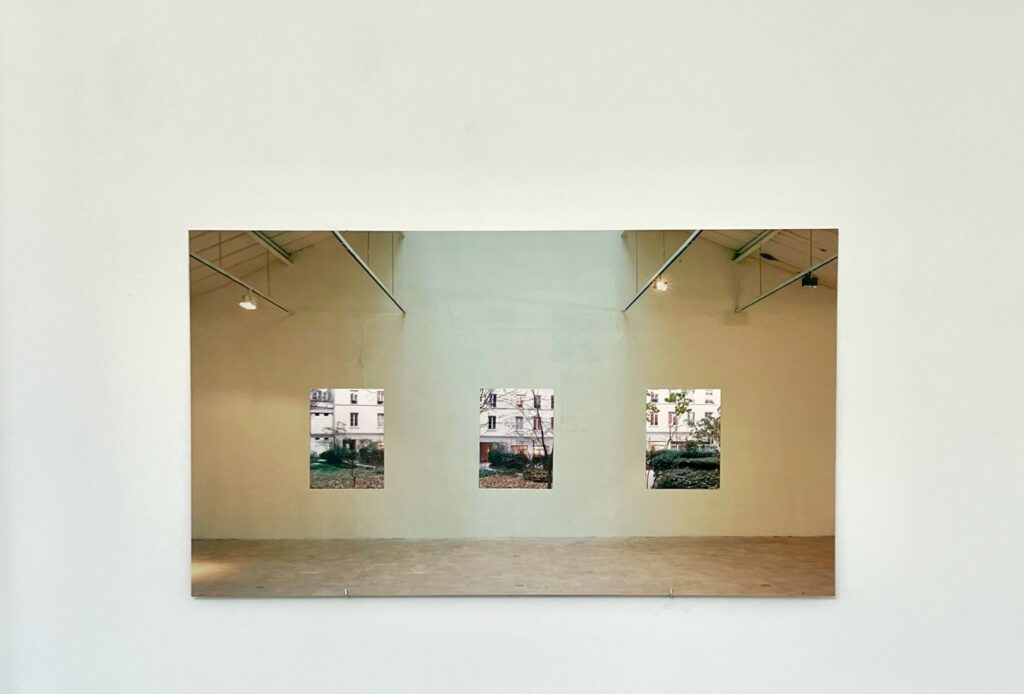

Forse, al fondo, la dialettica è, una volta di più, quella fra interiorità (del corpo ma anche del sé, di un luogo ma anche di un’istituzione) ed esteriorità. Proprio in relazione a quest’ultimo aspetto, Pietroiusti ripropone in mostra alcune opere fotografiche storiche appartenenti alla serie “Finestre Vivita” del 1989/90. Così come il corpo umano può essere indagato e visto nelle sue strutture interne attraverso alcune delle tecniche mediche evocate in mostra, anche gli edifici e gli spazi possono essere traguardati dallo sguardo dell’artista e svelare realtà altrimenti invisibili.

Un particolare ringraziamento ad Alex Paniz.

SCHEDA INFORMATIVA

MOSTRA: Cesare Pietroiusti – Materia paterna

LUOGO: The Gallery Apart – Via Francesco Negri, 43, Roma

INAUGURAZIONE: 02/04/2025

DURATA MOSTRA: 03/04/2025 – 31/05/2025

ORARI MOSTRA: dal martedì al venerdì 15,00 – 19,00 e su appuntamento

INFORMAZIONI: The Gallery Apart – tel/fax 0668809863 – info@thegalleryapart.it – www.thegalleryapart.it

CESARE PIETROIUSTI:

Nato nel 1955, vive e lavora a Roma. Si è laureato in Medicina con tesi in Clinica Psichiatrica nel 1979.Nello stesso anno è stato co-fondatore del Centro Studi Jartrakor e, nel 1980, della Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte, Roma. La ricerca artistica di Cesare Pietroiusti esprime interesse per le situazioni paradossali o problematiche nascoste nelle pieghe dell’ordinarietà dell’esistenza: pensieri che vengono in mente senza un motivo apparente, piccole preoccupazioni, quasi-ossessioni considerate troppo insignificanti per diventare motivo di analisi, o di auto-rappresentazione. Nel 1997 ha raccolto in una pubblicazione i Pensieri non funzionali, un centinaio di idee parassite, incongrue o comunque prive di scopo apparente, formulate come istruzioni per realizzare progetti artistici. Negli ultimi anni il suo lavoro si è concentrato soprattutto sul tema dello scambio e sugli ordinamenti economici. Pietroiusti è stato uno dei coordinatori delle residenze e dei progetti Oreste (1997-2001) e del convegno Come spiegare a mia madre che ciò che faccio serve a qualcosa? (Link, Bologna 1997). È inoltre co-fondatore di Nomads & Residents, New York, (2000), curatore CSAV, Fondazione Ratti, Como (2006-2011), docente di “Laboratorio Arti Visive”, IUAV, Venezia (2004– in corso); NABA Nuova accademia di Belle arti Roma (2021-in corso), MFA Faculty, LUCAD, Lesley University, Boston (2009-2016). È co-fondatore e Presidente della Fondazione Lac o Le Mon, San Cesario di Lecce, dal 2015. Da giugno 2018 a luglio 2022 è stato Presidente dell’Azienda Speciale PalaExpo di Roma.

ENG

The Gallery Apart is proud to announce “Materia paterna“, the second solo exhibition of Cesare Pietroiusti in the gallery spaces.

Grounded on the previous exhibition “Valori”, which partially focused on the complexity of the father/son relationship filtered through his father’s stamp collection, Pietroiusti investigates his relationship with his parents even more deeply, blatantly with respect to the father figure, but with a significant reference to his mother, ironically evoked through the term “materia”. Nothing can serve as an introduction to the exhibition better than the text written for the occasion by the artist.

The decision to devote an exhibition to the father figure –- not to the father in general, but to one’s own father – demands a chance, after deducting all of probable unconscious determinants.

In this case, it was the fact that I had to empty out, after selling it, the apartment on Via Novara, in the “posh” Trieste neighborhood of Rome, a short walk from the Macro Museum, where my maternal grandparents and, from my birth onward, my parents had lived. In that house my grandfather died in 1963, my grandmother in 1986, my father in 2011, and my mother four years ago. All the rooms were filled with objects whose stories, functions, appearances, spanned three generations – from the early to the last years of the 20th century. I threw out much, but much I kept, hoping to find interesting or surprising documents, perhaps able to shed light on aspects unknown to me about some family member. Thus, in the basement, in a couple of voluminous boxes covered with black soot, I found hundreds of documents about the scientific publications (1960-1966) of my father, Guido Pietroiusti.

Guido was a physician, a successful gynecologist (but he preferred to call himself “obstetrician”), long chief physician, in the happiest years of his professional life, of the Velletri Hospital. He was not a great speaker, nor a refined intellectual, but he was certainly an excellent doctor, highly respected and loved by his patients. I remember, in particular, his ability to reassure the parturients in the decisive moments of labor. He was convinced that I would also be an obstetrician, and when – I think I was in my second year of university and, incidentally, very late in my sexual maturation – he took me to his department and tried to teach me how to do a gynecological examination, I was overwhelmed with embarrassment, a sense of inadequacy and an unbridgeable distance between me (my fingers) and the possibility of making any kind of sense of what I was doing. Indeed, that distance has never been bridged, and perhaps the fact that I have been an artist and not a doctor is also due to that trauma.

Some of my father’s publications tell of a new technique learned in France, the celioscopy: a way, later to become very common, of exploring the female genital apparatus by “endoscopic means” by drilling a hole in the abdomen and passing a small lens through it connected to a photo- or video-camera. In the publication “The Importance of Celioscopy in Gynecologic Diagnostics,” the technique is illustrated both with color images of the internal organs and with some black-and-white photos of the surgical setting, in one of which my father is seen with his eye glued to a camera precariously connected to a tube that penetrates the abdomen of a person under general anesthesia, whose body is, otherwise, covered. This image, and the series of “celiophotos” reproduced in this and other files, reminded me that, between 1989 and the mid-1990s, I had exhibited, on various occasions in galleries and museums, photographic reproductions of what was on the other side of the walls of exhibition spaces.

The project of this “Materia Paterna” exhibition thus emerges from the idea of a comparison, and perhaps an attempt to shape an affinity that, given the obvious distance with respect to professional choices and values, is -– at least for me – unexpected and surprising.

“Materia paterna” thus becomes a project that lies between homage and the critical underlining of a substantial difference, between nostalgia and the irony of retracing a story punctuated by shreds of memory, through the reuse, manipulation, and re-configuration of objects otherwise meant to be thrown away in a dump. As if art could, with a freedom that not even scientific research possesses, make sense of otherwise incomprehensible or unwieldy, unserviceable or untouchable matter.

The exhibition presents a large body of works, some historical but mostly new production. As if to certify the trait d’union with the previous gallery exhibition, the artist has created a large-scale work consisting of two collages placed against each other, like two sides of a huge envelope, and containing respectively dozens of postal wrappers from auction houses or stamp dealers and dozens of letters and invoices attesting to his father’s acquisitions for his collection.

Much of the exhibition focuses on his father’s medical activities. Having found a substantial number of his father’s publications and books from his library, Pietroiusti used the scientific publications to create a large collage in which repetition and bichromy give rise to a work somewhere between conceptual and abstract-geometric, while the books have taken on new life in a series of volumetrically regular sculptures.

A photographic series, on the other hand, is based on the reproduction of images found by the artist and made by his father using the technique of celioscopy. Internal organs are revealed as the scene of enigmatic beauty, giving rise to images that evoke sidereal space. Directly connected, the sculptural work obtained by lining up, according to a dimensional progression from small to large, a series of steel uterine dilators, positioned to compose a sort of ascending staircase. And again through the use of objects found in his father’s studio, here is a work consisting of a sequential projection of 80 slides all titled GYNECOLOGY presumably used for educational purposes.

This body of work that reuses residual objects from his father’s long professional activity offers Pietroiusti an opportunity for an analysis of himself and his (failed) relationship with medicine, but it also prompts reflection on the female body, its centrality to the known universe and the miracle of life (think of Courbet’s L’origine du monde) but also on the dialectic between the traditional and patriarchal view of femininity as a mystery and the internalized awareness of the principle of women’s self-determination of their own bodies.

Perhaps, in the end, the dialectic is, once again, between interiority (of the body but also of the self, of a place but also of an institution) and exteriority. Precisely in relation to this latter aspect, Pietroiusti reproposes in the exhibition some historical photographic works belonging to the series “Finestre Vivita” from 1989/90. Just as the human body can be investigated and seen in its internal structures through some of the medical techniques evoked in the exhibition, buildings and spaces can also be transfixed by the artist’s gaze and reveal otherwise invisible realities.

A special thanks to Alex Paniz.

INFO

EXHIBITION: Cesare Pietroiusti – Materia Paterna

PLACE: The Gallery Apart – Via Francesco Negri, 43, Rome

INAUGURATION: 02/04/2025

EXHIBITION DURATION: 03/04/2025 – 31/05/2025

EXHIBITION HOURS: Tuesday through Friday 3 p.m. – 7 p.m. and by appointment

INFORMATION: The Gallery Apart – tel/fax 0668809863 – info@thegalleryapart.it – www.thegalleryapart.it

CESARE PIETROIUSTI:

Born in 1955, he lives and works in Rome. He graduated in Medicine with a thesis in Clinical Psychiatry in 1979. In the same year he co-founded the Centro Studi Jartrakor and, in 1980, the Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte, Rome. Cesare Pietroiusti’s artistic research expresses interest in paradoxical or problematic situations hidden in the folds of the ordinariness of existence: thoughts that come to mind for no apparent reason, small preoccupations, almost-obsessions considered too insignificant to become grounds for analysis, or self-representation. In 1997 he collected in a publication Pensieri Non Funzionali, a hundred or so parasitic ideas, incongruous or otherwise without apparent purpose, formulated as instructions for making artistic projects. In recent years his work has focused mainly on the concept of trade and economic orders. Pietroiusti was one of the coordinators of the Oreste residencies and projects (1997-2001) and of the conference Come spiegare a mia madre che ciò che faccio serve a qualcosa? (Link, Bologna 1997). He is also co-founder of Nomads & Residents, New York, (2000), CSAV curator, Fondazione Ratti, Como (2006-2011), professor of “Visual Arts Laboratory,” IUAV, Venice (2004-ongoing); NABA Nuova accademia di Belle arti Roma (2021-ongoing), MFA Faculty, LUCAD, Lesley University, Boston (2009-2016). He has been co-founder and president of Lac o Le Mon Foundation, San Cesario di Lecce, since 2015. From June 2018 to July 2022, he served as President of Azienda Speciale PalaExpo, Rome.

share on